Photo by Caleb Woods on Unsplash

Editor's Note: This article discusses reactions to trauma and may be triggering for some readers. It also contains spoilers for the book Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte.

"You think I have no feelings, and that I can do without one bit of love or kindness; but I cannot live so: and you have no pity."

-- Charlotte Bronte, Jane Eyre

Jane Eyre, by Charlotte Bronte, is the fictional story of a young girl who experiences parental loss, abuse and poverty. When we first meet Jane, she has already lost her parents; they died shortly after she was born. Although Jane's aunt takes her in, she experiences little kindness from her relatives. Jane's aunt displays blatant favoritism for her biological children, allows them to torment Jane, and consistently reminds Jane of her “lesser-than” status in the family and society. Only her nursemaid shows Jane kindness in her earliest years.

Although considered by many to be one of the greatest romances of all time, others see the Jane Eyre's relationship with Mr. Rochester as an example of emotional abuse and manipulation (e.g., Gaskell, 2021). In this perspective, Jane's attachment experiences laid the groundwork for a toxic relationship. According to attachment theory, we form relationships that re-enact our earliest experiences; if we experience abandonment, abuse, and manipulation with our early caregivers, we may later find ourselves in relationships that repeat these dynamics.

Jane Eyre's early years illustrate attachment trauma, the third pathway to dissociative hypoarousal. Attachment trauma describes separation, neglect, or abuse that occurs early in life. Specifically, the period of birth through the second year, or the time of infancy through toddlerhood.

It may surprise you to learn that even at the earliest ages we can observe evidence both of a fragmented self and enduring hypoarousal. How can an infant or small child, who does not yet have a fully developed sense of self, develop a split self? And, how is it possible for someone as young as an infant to experience enduring immobilization? The answer lies within our relaitonships with caregivers.

The caregiver relationship plays a vital role in determining whether an infant develops in a healthy way (e.g., Schore, 2003). Attuned caregivers accurately read a child's cues. They can tell when the child needs to eat or sleep and what emotions they feel. Attuned caregivers respond to those needs -- they help the child fall asleep when tired, understand the child's eating preferences, and soothe them when they become agitated. (Don't worry parents, caregivers do not need to attune perfectly to a child at every moment for healthy attachment to occur.)

When caregivers fail to recognize their child's needs too often and/or fail to respond adequately to those needs, children have fewer tools for calming themselves and engaging with others comfortably. These children experience misattuned caregiving.

Children of misattuned caregivers too often remain in a painful state that they don't know how to get out of. Like adults, infants can regularly feel hyper-aroused, hypo-aroused, or experience a biphasic response. Infants who experience prolonged dorsal vagal response show signs of infant dissociative hypoarousal. They appear detached, apathetic, dazed, blank and silent. They may suddenly become still or collapse. Such infants lack facial expressions, do not vocalize, and avoid eye contact (Schore, 2003).

Attachment theorists categorize infant attachment as secure (interdependent), anxious (dependent), avoidant (overly independent), and disorganized (fearful). Ogden and Fisher (2015) suggest that an avoidant attachment style leads to a tendency toward hypoarousal. Infants who develop avoidant attachment grew up with the internalized message that “I am on my own.” As a result, they feel uncomfortable reaching out to others. To self-regulate, they rely on a state of low arousal and low interpersonal stimulation. They withdraw from others to cope with stress, minimally express emotions and rely only on themselves for emotion regulation. They “usually find it difficult to shift out of low arousal states” (Ogden and Fisher, 2015; p. 32).

Caregiver misattunement leads to more frequent hypoarousal later in life, particularly alterations of consciousness (Lyons-Ruth et al., 2006). Subtle caregiver behaviors strongly predict dissociative experiences later in life including pulling away from emotional interaction with babies, not responding to a baby's attempts to engage, contradictory or confusing behavior, or appearing frightened of the baby. Researchers observed that caregivers who appeared fragile and timid had children who experienced more alterations of consciousness in adulthood. Their hesitancy likely confused infants as they learned to make sense of their world. Each of these problematic behaviors occurred subtly and could be easily missed.

Lyons-Ruth et al. (2006) called these elusive caregiver behaviors “Hidden Traumas.” Another hidden trauma that predicted dissociation involved caregivers wanting the infant to care for the caregiver’s emotions, rather than vice versa. Infants of hesitant or insecure caregivers may sense that their own survival depends on their caregiver being okay, so they focus on trying to make their caregiver okay. They learn to organize their lives according to their caregiver’s needs. As they grow, these children struggle to identify their own emotions or identify their own needs, a condition known as alexithymia. (van der Kolk, 2014)

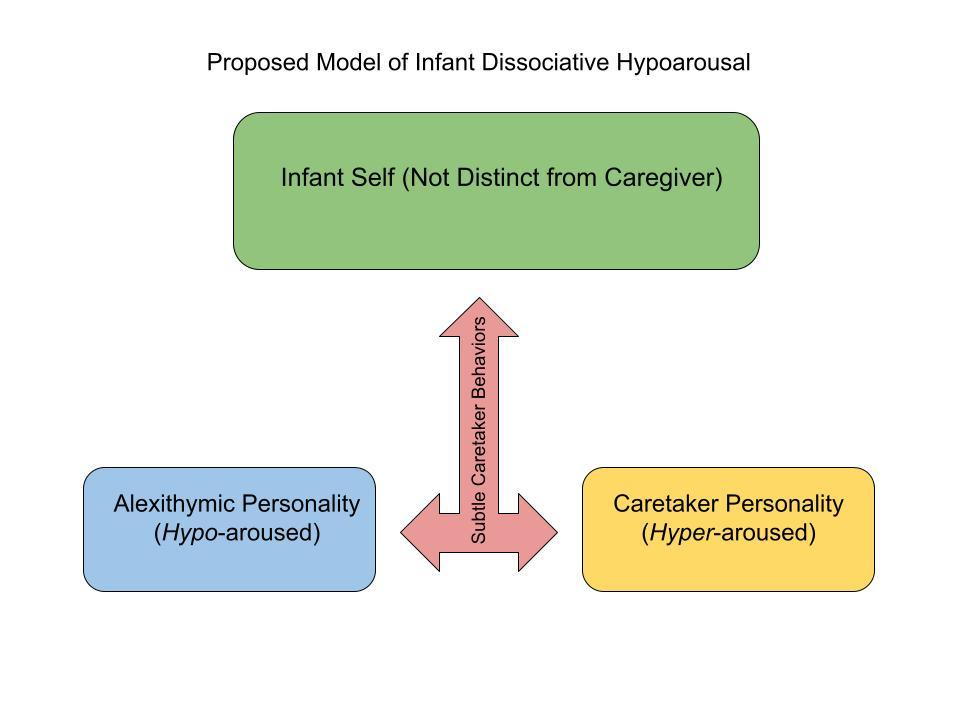

The infant suffering from hidden trauma grows up with a split self. One part of the self favors hypoarousal (alexithymic personality) and the other takes care of the misattuned caregiver (caretaker personality). These children may alternate between feeling highly anxious for the caregiver's happiness and well-being on the one hand with being withdrawn and shut down on the other. I propose the following model to describe dissociative hypoarousal for children of hidden traumas in their earliest years of life.

Even these children, whose trauma occurs in the earliest years of life, can recover. Children and adults can learn to attune to their own body sensations and emotional reactions, recognizing the cues that their caregivers could not. In doing so, they can learn to care for themselves first, before choosing to help others.

The Third Pathway shows how a splitting of the self (First Pathway) and enduring immobilization response (Second Pathway) coexist in a single, traumatized individual. Both conditions can be observed in brain studies of trauma survivors. My next article goes into more depth about research that demonstrates how splits in the self manifest as isolated brain systems.

The content of this blog is for informational purposes only and is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any condition or disease. This blog is not intended as a substitute for consultation with a licensed practitioner. Please consult with your own therapist or healthcare provider regarding any suggestions and/or recommendations made in this blog. Although the author has made every effort to ensure that the information in this blog was correct at publication time and while this publication is designed to provide accurate information in regard to the subject mater covered, the author assumes no responsibility for errors, inaccuracies, omissions, or any other inconsistencies herein and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions. Unless otherwise indicated by name or direct reference, any resemblance to persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental. The use of this blog implies your acceptance of this disclaimer.

Gaskell, D. (2021). Why Jane Eyre is not a romance and why we need to revisit this feminist classic. Books Are Our Superpower. https://baos.pub/why-jane-eyre-is-not-a-romance-1ed3f98bc474

Lyons-Ruth, K., Dutra, L., Schuder, M.R., & Bianchi, I. (2006). From infant attachment disorganization to adult attachment: Relational adaptations or traumatic experiences? Psychiatry Clinical North America. 29(1) 63-viii, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2005.10.1016.

Ogden, P. & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment. Norton.

Schore A. (2003). Affect Dysregulation and Disorders of the Self. Norton.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps The Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books.

© Nancy B. Sherrod, PhD