Photo by Avel Chuklanov on Unsplash

Editor's Note: This article discusses reactions to trauma and may be triggering for some readers.

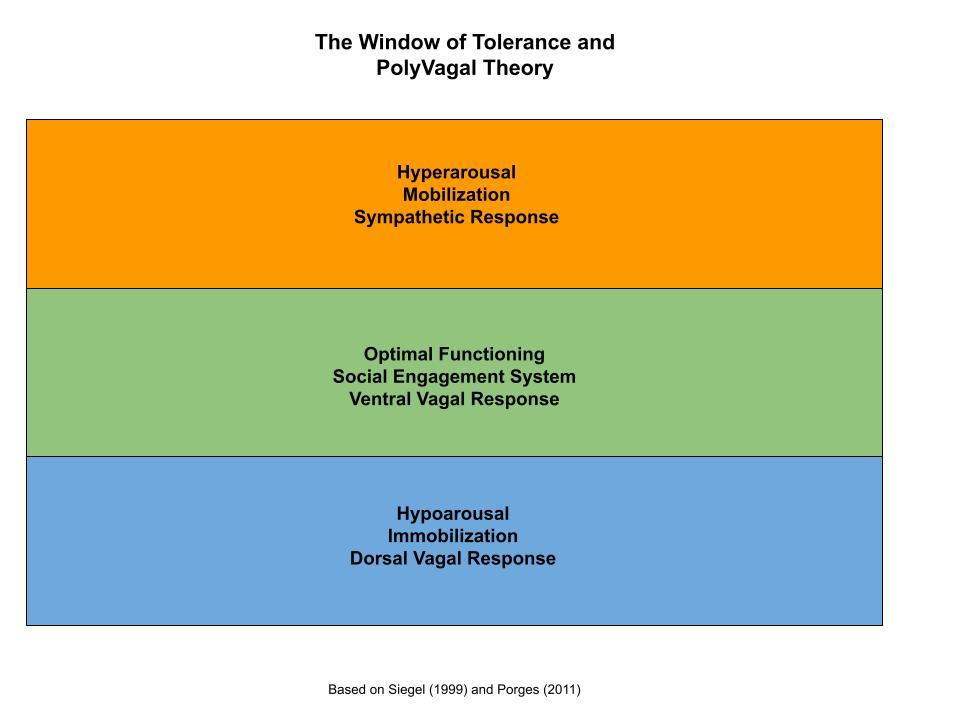

A lot of excitement about The PolyVagal Theory entered the mental health field recently. Why? The theory greatly expands our understanding of trauma responses and trauma survivor's experiences. Stephen Porges developed The PolyVagal Theory based on four decades of research on the nervous system (Porges, 2011). His theory challenges the commonly accepted paradigm of the human nervous system. Rather than two systems, the sympathetic and parasympathetic, Porges instead provides evidence of three systems. These three systems mirror human evolution. Porges calls the first system, most ancient and seen in vertebrate animals, the immobilization system. The second system, found in mammals and represented in the well-known “fight or flight” response manifests in the mobilization response. These responses can be applied to the window of tolerance model.

When we shift into immobilization or mobilization, we temporarily become dysregulated – not in control of our emotions and body reactions.

One of Porges’ most innovative contribution to models of stress and trauma lies in the third system, the social engagement system. When we exist in social engagement, we feel calm and regulated. In this state, we can communicate our needs with others and receive their support. PolyVagal Theory changes the way we look at “stress.” Rather than simply “managing” stress, as many of us have been encouraged to do, we can focus on how to move from hypo- and hyper-arousal into social engagement.

The immobilization system involves our unmyelinated dorsal vagus nerve and the brainstem. It bears the characteristics of hypoarousal that can be observed as lowered blood pressure, pauses in breathing and sometimes fainting or lightheadedness. Like other animals, human bodies flood with endogenous opioids when they judge a threat to be inescapable (Lanius, 2014). The dorsal vagal response involves a slowed metabolism and increased pain threshold, sometimes referred to as death feigning.

Imagine a mouse caught by an owl. As the owl takes off flying with the mouse in its talons, the mouse cannot escape. The mouse cannot fight or flee. Instead, it becomes limp, its body releases natural pain killers (opioids) so if the owl kills it, it will feel little pain. Though rarely hunted by lions or bears, human bodies contain the same survival responses as other vertebrates. We use dissociative hypoarousal when we have exhausted other survival options.

The dorsal vagal response shuts parts of the body down. The area of our brain in charge of creating a narrative of events, the thalamus, turns off. Much of the left brain, responsible for logical thought, also shuts down. The speech centers of the brain no longer operate. At the time of trauma, people exist purely in "speechless emotion" (van der Kolk, 2014). Similar body reactions return with trauma triggers. Our bodies travel back to the time when we originally felt immobilzed and we feel shut down again.

Many people experience a deeper collapse into hypoarousal once a threat passes, perhaps the body’s way of recuperating. In fact, Schore (1997) thinks of the immobilization response as a conservation response. When nervous systems become overwhelmed, immobilization disconnects the body from the experience of threat. Once disconnected, bodies can regroup and conserve energy.

Opposite to the immobilization response, the mobilization response involves the sympathetic nervious system. It requires the increased metabolism necessary for fight or flight. The mobilization system produces increased heart rate and involves many of the chemicals commonly associated with stress including cortico releasing hormone and cortisol. As with the immobilization response, mobilization restricts much of our communication. It is harder to listen to others. When speaking, we are more likely to use angry language and profanity (van der Kolk, 2014).

We interact much differently within the social engagement system. When humans shift into social engagement, their bodies shut off both the hypo- and hyper-arousal responses. Social engagement allows us to use our creativity and flexibility to master a threat. In a calm state that lies within the window of tolerance. Individuals use facial expressions, changes in vocal tone, and head movements to communicate. In this state, we can truly hear and listen to others.

The social engagement system involves the myelinated ventral vagus nerve found in humans and primates. Because of this, Porges refers to it as the ventral vagal response. The neurochemicals most associated with this system include oxytocin, involved in important social interactions such as caregiving and the building of trust.

For much of the last century, education about the immobilization response has taken a back seat to education about fight or flight. For decades, public health education and awareness raising efforts have focused a great deal on stress reduction and stress management. Understanding the equal importance of the immobilization and social engagement systems greatly broadens our understanding of our bodies’ responses to trauma. As I will discuss later, it also expands the range of trauma treatment options.

For the next article, however, I will discuss a more detailed breakdown of defense strategies.

The content of this blog is for informational purposes only and is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any condition or disease. This blog is not intended as a substitute for consultation with a licensed practitioner. Please consult with your own therapist or healthcare provider regarding any suggestions and/or recommendations made in this blog. Although the author has made every effort to ensure that the information in this blog was correct at publication time and while this publication is designed to provide accurate information in regard to the subject mater covered, the author assumes no responsibility for errors, inaccuracies, omissions, or any other inconsistencies herein and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions. Unless otherwise indicated by name or direct reference, any resemblance to persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental. The use of this blog implies your acceptance of this disclaimer.

The following sources were invaluable in writing the above article:

Lanius, U.F., Paulsen, S.L., & Corrigan, F.M. (2014). Neurobiology and the Treatment of Traumatic Dissociation: Toward an Embodied Self. Springer.

Porges, S.W. (2011). The PollyVagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. Norton.

Schore A. (2003). Affect Dysregulation and Disorders of the Self. Norton.

Siegel, D. (1999). The Developing Mind. Guilford.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps The Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books.

© Nancy B. Sherrod, PhD