Photo by Joshua Fuller on Unsplash

Editor's Note: This article discusses reactions to trauma and may be triggering for some readers.

By the time we encounter Harry in Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, he has already endured much trauma. He has lost loved ones, lived with cruel and neglectful relatives, and witnessed the murder of one of his schoolmates. Much of the time, he fights. But occasionally, he collapses into what appears to be dissociative hypoarousal.

"So it went on for three whole days. Harry was filled alternately with restless energy that made him unable to settle to anything, during which he paced his bedroom again, furious at the whole lot of them for leaving him to stew in this mess, and with a lethargy so complete that he could lie on his bed for an hour at a time, staring dazedly into space..." (Rowling, 2003; p.44)

Well-known trauma researcher, Bessel Van Der Kolk, recognized that people with trauma histories tend to alternate between hyper-arousal and hypo-arousal in what he called the biphasic response to trauma (van der Kolk & Saporta, 1991).

When a trauma survivor feels threatened, their body automatically goes into an animal defense response. If they can run away or defend themselves (fight vs. flight), their body will take action. As with Harry, hyper-arousal can take the form of anger, restessness, and an inability to calm. Most people understand the feelings associated with hyper-arousal -- the sense of fear, panic or anger that comes with the fight or flight response. But fewer people have awareness of the numbness, collapsed or shut down feelings that go with hypo-arousal. (Perhaps that is why it was difficult for me to find a pop culture example for this topic that did not involve someone using drugs or alcohol to numb themselves.)

Hypo-arousal comes in when fighting or fleeing are not options. The body releases endogenous opioids - natural heroin. A person feels numb, spacey, and “out of it” to protect themselves from the pain and overwhelm of hyperarousal. This hypoarousal defense is sometimes referred to as a dorsal vagal or immobilization response After trauma subsides, many survivors continue to use dissociative hypoarousal to cope.

Some people feel ashamed or angry at their tendency toward hypoarousal, wondering, Why do I shut down? Why can’t I talk or fight back. It can be helpful to know these responses originate from biological defenses. They are involuntary responses, seen in all vertebrate animals including humans and mammals.

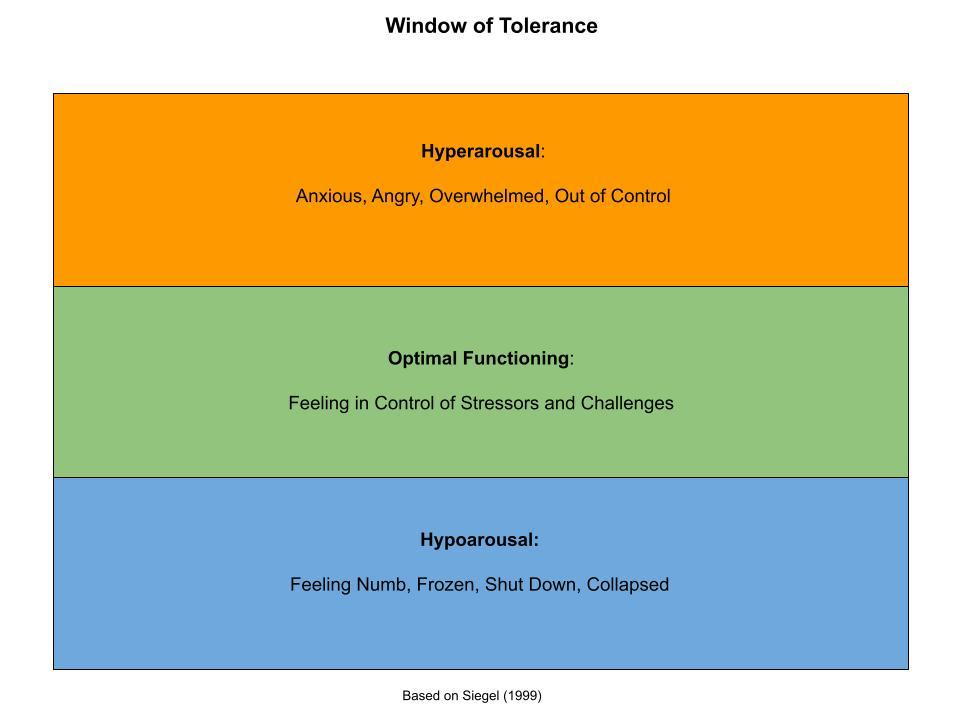

Originally developed by Dr. Dan Siegel, the window of tolerance model (illustrated below) shows a range of responses a person can have to stressful events (Siegel, 1999). Within the window of tolerance, a person experiences highs and lows, such as excitement or calm, but feels in control of those fluctuations. When a person’s arousal rises above their window of tolerance, they experience hyper-arousal, with extreme anxiety, fear and panic. They feel out of control. If, on the other hand, arousal falls below the window of tolerance, survivors experience hypo-arousal. In those In this case, the immobilzation response emerges.

Understanding the window of tolerance can help trauma survivors describe their reactions and overall functioning. A survivor can monitor how often they experience reactions that exceed or fall below the window.

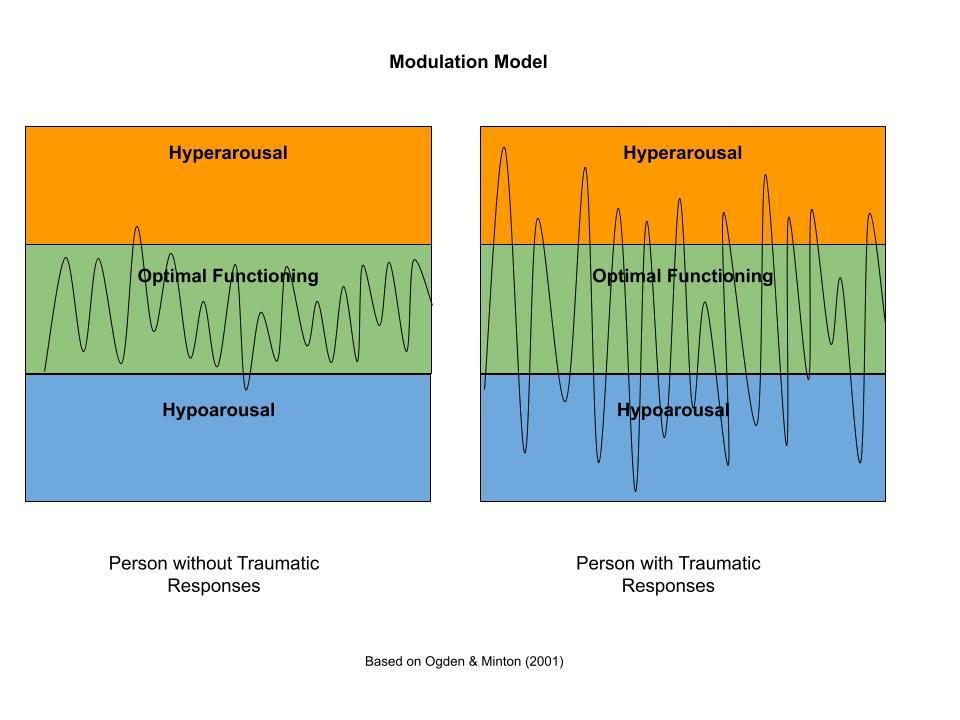

Pat Ogden and Kekuni Minton’s (2001) Modulation Model explains differences between non-trauma responses and biphasic trauma survivor responses. Someone without trauma will experience ups and downs in mood or activation, but mostly within their window of tolerance. Occasional swings outside the window quickly regulate back within the window. But a traumatized person attempting to self-regulate swings up and down between extremes of hyper and hypoarousal, making it biphasic.

People who struggle after trauma often alternate between extremes of hyper- and hypo-arousal as though their bodies search for some sort of balance. Many survivors long for a sense of peace and control that exists within the window of tolerance. A first step in moving toward that balance involves understanding the full spectrum of their responses.

To that end, in my next article, I explore more about the biological factors in dissociative hypoarousal by focusing on The Polyvagal Theory.

The content of this blog is for informational purposes only and is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any condition or disease. This blog is not intended as a substitute for consultation with a licensed practitioner. Please consult with your own therapist or healthcare provider regarding any suggestions and/or recommendations made in this blog. Although the author has made every effort to ensure that the information in this blog was correct at publication time and while this publication is designed to provide accurate information in regard to the subject mater covered, the author assumes no responsibility for errors, inaccuracies, omissions, or any other inconsistencies herein and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions. Unless otherwise indicated by name or direct reference, any resemblance to persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental. The use of this blog implies your acceptance of this disclaimer.

The following sources were invaluable in writing the above article:

Ogden, P. And Minton, K. (2001). The modulation model: Effects of unmodulated arousal on information processing. In. Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Training Institute: Sensorimotor Psychotherapy Training for Trauma Treatment Manual & Workbook. [Unpublished training materials].

Rowling, J.K. (2003). Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. Arthur A. Levine, Scholastic.

Siegel, D. (1999). The Developing Mind. Guilford.

Van der Kolk, B.A. and Saporta, J. (1991). The biological response to psychic trauma: Mechanisms and treatment for psychic numbing. Anxiety Research (U.K.). 4:199-212.

© Nancy B. Sherrod, PhD