Editor's Note: This article discusses reactions to trauma and may be triggering for some readers.

If you have ever felt frozen, you recognize this experience. Your heart pounds and your muscles tense up with anxiety as though you are prepared to escape or resist. Yet in that moment you feel as though you cannot move, no matter how much you want to. This strange and often frustrating experience can be explained by a deeper look at our human defense strategies.

Theorists now recognize a variety of human defensive responses beyond fight and flight that include freeze, avoidance, withdrawal, hiding, cringing, submission and help-seeking. Many of these responses are complex, and involve combinations of the main defensive systems -- Mobilization, Immobilization and Social Engagement.

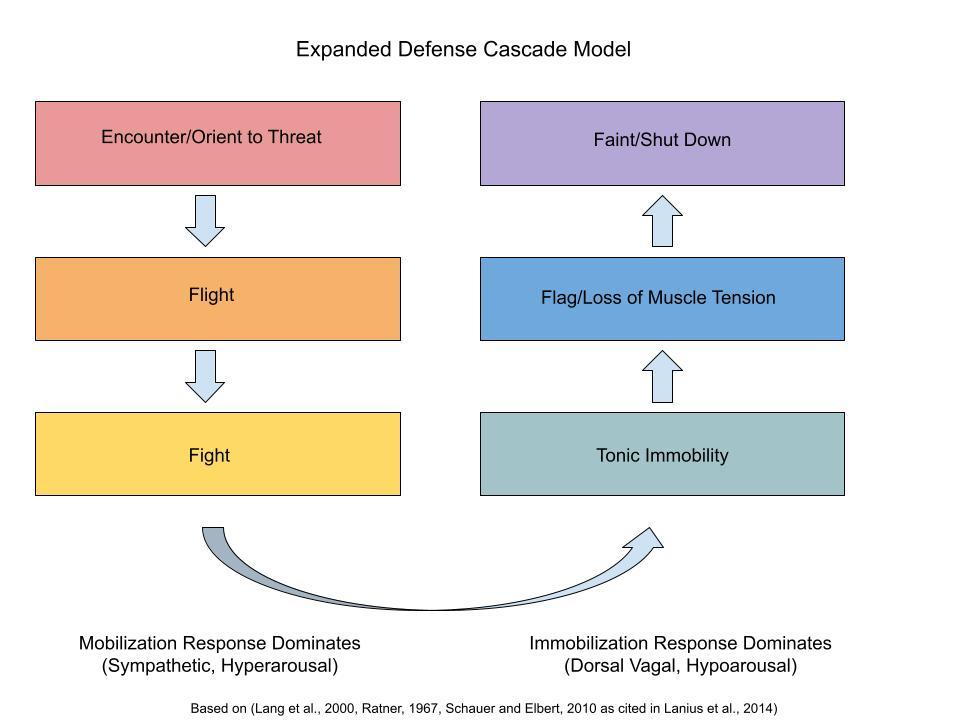

Theorists developed a four-stage Defense Cascade Model to show the sequence of defenses animals and humans typically pass through when they encounter threat (Lang et al., 2000, Ratner, 1967 as cited in Lanius et al., 2014). Schauer and Elbert (2010 as cited in Lanius et al., 2014) offer an expanded 6-stage model. These models explain more nuanced responses within the broader categories of hyper- and hypoarousal. The illustration below is based on these models.

At the earliest stage, encounter, we stop to assess the threat before us. If we confirm that a threat exists, we attempt to flee. When flight is not possible, we attempt to fight. When neither of these can happen, our bodies remain prepared for fight or flight internally, while holding still, waiting for an opportunity. We freeze. For example, a herd animal under attack by a predator may initallly stay very still. When it sees an opportunity to escape, the animal will suddenly flee. Escape would not be possible without having the mobilzation response at the ready (Levine, 1997, 2010).

Theorists suggest that the freeze response involves a combination of hyper- and hypoarousal. For example, Schore (2008) proposes that during freeze, a person experiences a dominant immoblization response on top of a weaker mobilization response, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as tonic immobility. This accounts for the strange feeling that part of you wants to run but at the same time, your feet feel nailed to the floor.

Schauer and Ebert (2010, cited in Lanius, 2014) refer to a number of human defensive responses that fall under the umbrella of tonic immobility aside from freezing. During tonic immobility, a person may withdraw, hide, or cringe for self-protection. A person is still, but also, ready to fight or flee if the chance arises.

Levine (1997, 2010) proposes that we can only maintain tonic immobility for so long. After awhile, prolonged inescapability leads to feelings of helplessness. Prolonged helplessness, in turn, leads to deeper states of hypoarousal, such as numbness or shutting down People lose their muscle tone and begin to flag (Schafer and Ebert, 2010 cited in Lanius, 2014). At this point no sympathetic response remains. As a person moves deeper into hypoarousal, they become more and more likely to appear shut down. Meanwhile, internally, they often experience alterations or lowering of consciousness. In the deepest expression of hypoarousal, a person loses consciousness altogether (fainting).

If instead, humans move out of freeze, they can discharge the intense mobilization energy that has been locked inside. When humans are able to discharge that energy, they do not develop posttraumatic stress symptoms (Levine 1997, 2010). Unlike animals, however, humans struggle to move out of tonic immobility. We hope we can simply move forward with our lives and put trauma behind us. The problem is, trauma does not simply go away because we try not to think about it. Instead, it lives on in our bodies.

Trauma that lives on in our bodies manifests as parts. In my next article, I describe fragmentation into parts following trauma.

The content of this blog is for informational purposes only and is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any condition or disease. This blog is not intended as a substitute for consultation with a licensed practitioner. Please consult with your own therapist or healthcare provider regarding any suggestions and/or recommendations made in this blog. Although the author has made every effort to ensure that the information in this blog was correct at publication time and while this publication is designed to provide accurate information in regard to the subject mater covered, the author assumes no responsibility for errors, inaccuracies, omissions, or any other inconsistencies herein and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions. Unless otherwise indicated by name or direct reference, any resemblance to persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental. The use of this blog implies your acceptance of this disclaimer.

The following sources were invaluable in writing the above article:

Lanius, U.F., Paulsen, S.L., & Corrigan, F.M. (2014). Neurobiology and the Treatment of Traumatic Dissociation: Toward an Embodied Self. Springer.

Levine, P.A. (1997). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. North Atlantic Books.

Levine, P.A. (2010) In An Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness. North Atlantic Books; ERGOS Institute Press.

Porges, S.W. (2011). The PollyVagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. Norton.

Schore A. (2003). Affect Dysregulation and Disorders of the Self. Norton.

© Nancy B. Sherrod, PhD