Photo by Pavan Trikutam on Unsplash

Editor's Note: This article discusses reactions to trauma and may be triggering for some readers.

"I felt just like I did at the time of the accident. I felt nothing."

--Bessel Van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma

As “Ute” recalled how she felt at the time of her car accident, Bessel van der Kolk measured her brain activity. He writes, “her mind went blank, and nearly every area of her brain showed markedly decreased activity" (van der Kolk, 2014; p. 71). He describes what dissociative hypoarousal looks like in the brain -- diminished activity. It makes sense that hypoarousal shows up as low activity. But what about the fragmentation of dissociation? How might that show up in the brain?

Lanius, Paulsen and Corrigan (2014) propose that splits in the self that occur due to trauma result from problems in the way that important areas of the brain communicate with one another. In ordinary circumstances, brain areas communicate to carry out numerous tasks and process information. For instance, the human brain can filter out stimuli to focus on what is most important in the environment. It can also record memories in a way that serves a person's growth and development (Lanius, Paulsen and Corrigan, 2014).

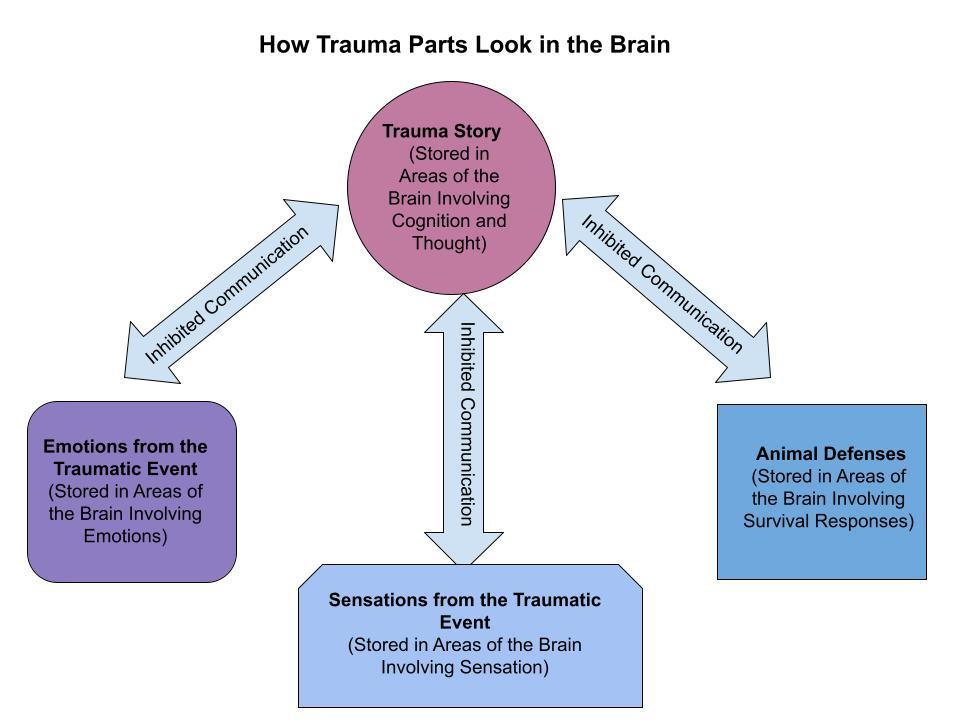

When these parts don't talk to one another, they function somewhat independently. Just as trauma results in a personality with discrete parts, the brain of a traumatized individual has parts that function separately. Each part contains a different aspect of the trauma, as proposed in the diagram below.

Van Der Kolk (2021) observed that most trauma survivors can tell a story about their trauma. Meanwhile, other aspects of the trauma, such as sensations and emotions, may be split off into other areas of the brain. For example, a particular smell (sensation) may associate with panic and fear (emotion), but a person may not know why. These body memories don't make it into the trauma story. Certain areas activate only with specific triggers, explaining the experience of emotional hijacking.

How does hypoarousal inhibit communication between areas of the brain? Some of the body's natural chemicals, in particular the endogenous opioids, release during the hypoarousal response. Endogenous opioids supress areas of the brain. After someone experiences the hypoarousal defense, endogenous opioids flow to parts of the brain and inhibit them. Researchers also believe that endogenous opioids cause alterations and lowering of consciousness by modifying communication among areas of the brain (Lanius, Paulsen and Corrigan, 2014).

Our brainstem contains areas that control survival functions including breathing, heart rate, swallowing and maintaining balance. Meanwhile, the cortex manages our conscious thoughts. When these two areas fail to communicate effectively, a person struggles with conscious awareness of their bodies. This phenomenon may account for the alexithymia observed in many trauma survivors.

Many trauma survivors struggle to find the language to fully express their experiences. This likely occurs because so much of traumatic reactions manifest on the right side of the brain (Schore, 2006; van der Kolk, 2014). Meanwhile, language functions are based primarily on the left side. Lanius, Paulsen and Corrigan (2014) propose that hypoarousal from trauma suppresses the communication between the right and left brain hemispheres along the corpus collosum, which would explain why survivors feel cut off from their words -- another form of splitting into parts.

As an EMDR practitioner, I have heard clients describe the therapy as one that connects them with inaccessible or forgotten parts of their brain. Accessing these parts provides them with the ability to move through trauma, rather than remaining trapped in it. EMDR is just one example of a trauma therapy that can help survivors re-integrate parts at the biological level.

In my next article, I continue my discussion of trauma and parts with a discussion of Complex PTSD and secondary dissociation.

The content of this blog is for informational purposes only and is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any condition or disease. This blog is not intended as a substitute for consultation with a licensed practitioner. Please consult with your own therapist or healthcare provider regarding any suggestions and/or recommendations made in this blog. Although the author has made every effort to ensure that the information in this blog was correct at publication time and while this publication is designed to provide accurate information in regard to the subject mater covered, the author assumes no responsibility for errors, inaccuracies, omissions, or any other inconsistencies herein and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions. Unless otherwise indicated by name or direct reference, any resemblance to persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental. The use of this blog implies your acceptance of this disclaimer.

References

Lanius, U.F., Paulsen, S.L., & Corrigan, F.M. (2014). Neurobiology and the Treatment of Traumatic Dissociation: Toward an Embodied Self. Springer.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps The Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books.

Van der Kolk, B. (2021). 2-day Trauma Conference: The Body Keeps the Score- Trauma Healing with Bessel Van Der Kolk, MD. [Video]. PESI.

© Nancy B. Sherrod, PhD